European Plastics Industry: Upfront with growth, Brexit, Industry 4.0 - August digital issue

Also, download this story from the electronic issue here

Despite a host of issues, ranging from marine waste to multiple force majeures at materials suppliers, the European plastics industry is in a good state of health, against the backdrop of growth; Industry 4.0 and a circular economy. But a looming issue is that the recent Brexit vote may have turned the table for UK’s plastics industry, with the lack of skills to affect it in the future.

European machinery associations report slight growths

Europe is the world’s second largest producer of plastics after China and prospects appear to be improving, with trade associations reporting growth.

Even in Italy, where consumption has been flat at best for some time, equipment association Assocomaplast, at its recent annual assembly, reported that 2015 was a good year for most companies: while production increased, exports witnessed further growth to over EUR2.9 billion, exceeding the record set in 2007 (pre-crisis) for sales abroad.

Italy’s National Institute for Statistics (ISTAT) data on foreign trade of machinery, equipment and moulds for plastics and rubber for the first quarter of 2016 show stable exports, compared to the same period in 2015. This trend is attributable to equipment like extruders, flexographic printers, and injection moulding machines, says the association.

Geographically, a positive trend is noted in the EU markets (Spain +27%, Czech Republic +17%, UK +15%, France +14%), with the notable exception of Poland, where sales declined by 25% in the first quarter of 2015. A major export market for Italians, Germany, remained unchanged at just over EUR91 million. Meanwhile, sales declined to the US and especially Mexico, respectively, by 6% and 56%; while exports to Brazil tripled, approaching EUR20 million, while those to China remained stable at just under EUR30 million.

Meanwhile, Germany’s plastics and rubber machinery manufacturers association VDMA expects sales to increase by 2% in real terms in the current year with a further 2% rise anticipated for 2017. In 2015, output was up by 4.7% and exports were 1.6% higher. German plastics and rubber machinery exports went to 162 countries in 2015.

In terms of markets, it says that the US is the biggest, followed by China, Poland and Mexico. “Deliveries to Russia were down by a further 15%, India has bottomed out and there are also positive signs in all the countries of Southeast Asia.”

Although export volumes were slightly ahead of the previous year’s level (EUR4.7 billion), Germany’s share of the rapidly growing world trade in plastics and rubber machinery declined to 22.2%.

Challenges: unstable materials supply; high energy costs

Plastics processors across the continent last year found difficulties in obtaining raw materials. Several major polyolefin plants in Europe stood still for extended periods and global economic and trade framework conditions made it difficult for processors to obtain materials on international markets. These factors included not only the relative weak Euro against the US dollar, but also continued strong demand for plastics in Asia and the US. Indications are that price volatility should be lower this year, however.

The situation led to umbrella trade association European Plastics Converters (EuPC) establishing the Alliance for Polymers for Europe, to “provide detailed information on the current polymer market and help assist raw material users through its network of national plastics associations, as well as assist companies in requesting suspension of certain EU import duties to relieve shortages on polymer markets.” In February, The Polymers for Europe Alliance launched its online Europe-wide customers’ satisfaction survey to award the best polymer producers for Europe.

Energy costs are also very important for the whole of the plastics industry. Companies across the German industry have been particularly vocal in their complaints – prices are among the highest in Europe – and the German chemical industry is also concerned about its falling international competitiveness, especially versus North American companies who have the advantage of shale gas.

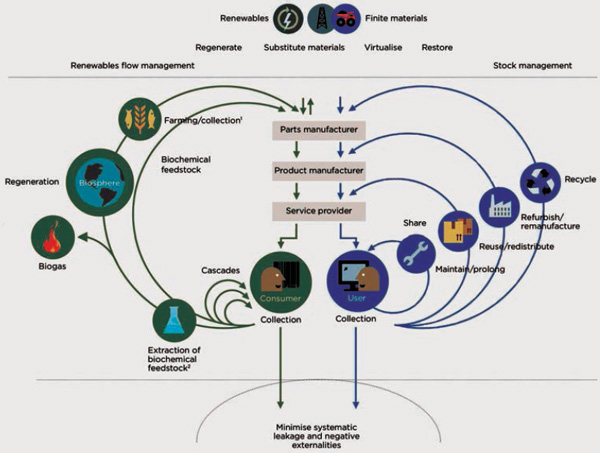

The circular economy

On top of concerns about materials and energy supply, there is also growing awareness in Europe that more needs to be done about use, reuse, and preservation of precious plastics. Late last year, the European Commission adopted what it says is an ambitious new “Circular Economy Package” (CEP), which it says will “contribute to closing the loop of product lifecycles through greater recycling and re-use, and bring benefits for both the environment and the economy.”

The Commission has proposed revisions to legislation on waste. Key elements include a common EU target for recycling 75% of packaging waste by 2030 and a ban on landfilling of separately collected waste.

“Less than 25% of plastic waste collected is recycled, and about 50% goes to landfill,” says the Commission.

PlasticsEurope has expressed concerns: "The European plastics industry has been calling for a legally binding landfill restriction on all recyclable as well as other recoverable post-consumer waste by 2025. Although a 10% target constitutes a step in the right direction, it remains a timid attempt to put an end to the landfilling of all waste which can be used a resource.”

European Bioplastics (EUBP), the trade association for suppliers of biobased plastics, was more enthusiastic about the report. It says that “forward looking sectors with strong environmental credentials and growth potential, such as bioplastics, need to be promoted.”

It predicts that by 2025 production capacities of bioplastics within the EU will have grown twentyfold to 5.7 million tonnes.

Not just a buzzword

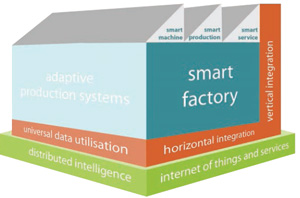

Despite all these concerns, the European plastics industry has its eyes firmly fixed on the future. Many European machinery companies are likely to have the number 4.0 highly visible on their stands at K2016 exhibition in Germany, to be held from 19-26 October, as they push their solutions for “smart” factories that operate within the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT).

The 4.0 refers to Industry 4.0, a term invented in Germany in reference to what is perceived as the fourth industrial revolution – and the German government’s plan to make sure German industry is at its forefront. Proponents of Industry 4.0 say it represents a paradigm shift from centralised to decentralised production.

For plastics processors, too, the digitisation of the industry and new digital technologies offer new perspectives and advantages.

UK’s plastics sector

The UK accounted for 7.7% of Europe’s overall plastics demand of 47.8 tonnes in 2014, based on trade association PlasticsEurope’s data. The UK uses over 5 million tonnes/year of plastics in the packaging, construction and automotive markets. As one of Europe’s top plastics processors, UK is estimated to produce approximately 2.5 million tonnes/ year of plastics raw materials.

The UK plastics sector, which comprises 3,000 primary processors, contributes £17.5 billion/year of sales value and provides employment to 180,000 workers or 7% of UK’s manufacturing workforce, according to the British Plastics Federation (BPF) study “UK Plastics Industry: A Strategic Manufacturing Sector”.

Yet, as the industry grows, the skills gap is widening. A general lack of training and apprenticeships, emergence of technologies and the appropriate skills needed are looming in the plastics manufacturing sector. The widening gap could become harder to fill now with the UK exiting from the European Union (EU) via the “Leave”/ Brexit vote in the recently concluded referendum.

Central to the Brexit issue has been the flow of migrants into the country. Even with foreign workers comprising part of its manufacturing workforce, the skills gap has been a dilemma for UK’s sector. In 2014, Britain's business secretary Vince Cable cautioned against workers not having the required ability and workers approaching retirement that needed to be replaced and how this could adversely impact the sector.

A recent Engineering Employers’ Federation (EEF) report finds that nearly four out of five, or 73% of UK manufacturing firms, are affected by a shortage of skills. The UK Commission for Employment and Skills (UKCES), a publicly-funded, industry-led organisation providing leadership on skills and employment issues across the UK, also reported of about 35% of ‘hard-to-fill’ vacancies in the manufacturing sector, which has persisted since 2013.

Meanwhile, managing consulting firm Deloitte Consulting’s 2014 study shows that of the top five European cities, London, England’s capital city, is targeted by 46.5% of highly skilled workers. London-based Senior Partner at Deloitte, Angus Knowles-Cutler, also opined that London is more central to the economy of Europe (than New York is to the economy of North America), and thus attracts the largest proportion of high-skilled talent.

According to the latest Office of National Statistics (ONS) data of the UK Labour Market report released 15 June, non- UK nationals working in UK stands at 3.34 million, an increase of 229,000 between January-March this year, against the same period a year ago. The increase reflects the admission of several new member states to the EU, ONS stated.

With the Brexit, EU workers in the UK could exit the country, thus causing a ripple effect to the pool of skills. This could mean wages and training/recruiting costs will have to increase to attract skilled workers. As well, UK will have to compete with lower cost of labour offered in Eastern Europe, for example. Conversely, immigration restrictions may be applied to EU workers wanting to work in the UK.

Dwindling vote of confidence for automotive makers

UK is an important financial and investment centre of Europe and preferred manufacturing base for some of the largest companies in the world. Deloitte states in its 2014 study that London hosts 40% of the world’s largest companies; while 60% of top non-European companies with European headquarters are based in London. The edge UK has as a gateway to investments for single-market Europe has dissolved with the Brexit, observers say.

Further, there is concern for businesses relocating elsewhere to Europe. France’s capital, Paris, which is the location for 19% of highly skilled workers in the EU, is stepping in and offering itself to international businesses at the crossroads of opting to relocate to either Dublin (Ireland), Frankfurt (Germany), or Paris, after the Brexit.

The automotive sector in the UK, which levers the island nation’s opportune business environment, is seen to be hit by the skills gap.

In the 2015 automotive analysis developed by the Automotive Council for the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), it was forecast that by 2020, the UK will be producing 2 million vehicles/year, a significant leap from the current total of 1.5 million vehicles/year. According to the report, over 5,000 jobs related to vehicle and engine producers could be created, along with up to 28,000 in the supply chain, by the early 2020s. The caveat is that these figures represent a scenario of UK remaining with the EU.

The report affirms that the number of jobs that would be created would translate to vacancies in the automotive sector. Not only will this situation lead to a disruption in business operations, but recruitment of critical positions, especially of skilled engineers, will become a challenge.

The report sets out a range of recommendations to tackle the skills shortage. These include the implementation of a co-ordinated approach to STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects in schools, as well businesses ensuring that apprenticeship opportunities on offer from the government are maximised.

The post-Brexit scenario, however, is different. Large automotive makers like General Motors, Ford and Toyota may take another way out by exiting the country. Being out of the EU could see export tariffs of vehicles rise by as much as 10% and for automotive parts, up to 2.7%. These could represent losses to UK-based car makers, and at worst, impede the competitiveness of UK’s automotive sector.

Patching up the skills gap

While skills are a backbone of the UK industry, there are other areas that may be strengthened to compensate for the skills gap. UK can leverage on advanced manufacturing that utilises enabling technologies and computerisation of production processes. The UKCES also recommends a “shift to shorter production runs and more tailored products, which is being driven by customer demand and facilitated by new manufacturing techniques such as 3D printing and plastic electronics.”

Reprioritising other key issues in the plastics industry could also deter the potential impact of the skills gap. Apart from developing a skilled and educated workforce, a number of other key issues are deemed critical to be addressed by stakeholders and the government. These include tapping on export opportunities and inward investment; access to a secure supply of feedstock at stable prices; sensible legislation and taxation to encourage growth and competitiveness; promoting the benefits of plastics, as well as countering misinformation about plastics; and intensifying R&D, according to BPF.

Lastly, for the nation that invented polyethylene in the 1930s, pioneered the use of polyester for the manufacture of PET, and which is a long-standing leader in technologies used in plastics-related industries, the UK has the cuttingedge capabilities for its plastics sector to remain buoyant. The industry may be in the midst of the Brexit storm, but that too can be weathered, say observers.

(PRA)Copyright (c) 2016 www.plasticsandrubberasia.com. All rights reserved.